It’s Your Park

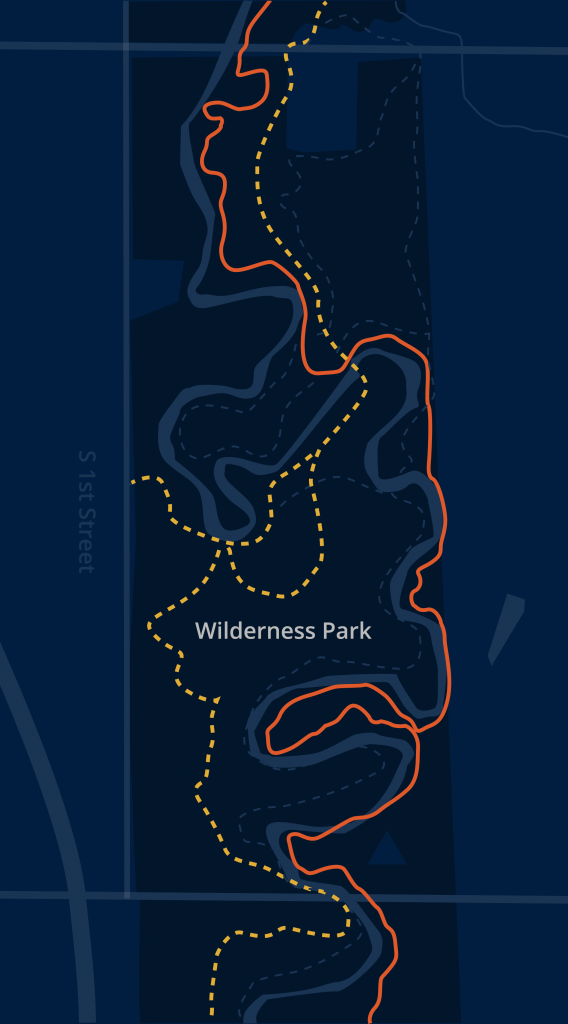

Wilderness Park is Lincoln’s largest public park. The seven-mile, linear, 1,472-acre woodland is nestled just west of the Jamaica North Trail along Salt Creek from Van Dorn to Saltillo. The park features 31 miles of hiking, cycling and horse trails within its naturally wooded landscape. The hiking trail was designated part of the National Recreation Trails Program in 1977.

Lincoln’s wildest park does not fit neatly into conventional definitions of parks and wilderness areas, but its uniqueness is what makes it special. For years, Wilderness Park’s dense forest, meadows and creek beds have protected Lincoln from serious flooding. Since Lancaster, NE (now Lincoln) was founded in 1856, Salt Creek has been a flooding threat. It still is, but since the Salt Creek Levee and ten upstream flood control structures were built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1960s, Salt Creek flooding in Lincoln is less frequent.

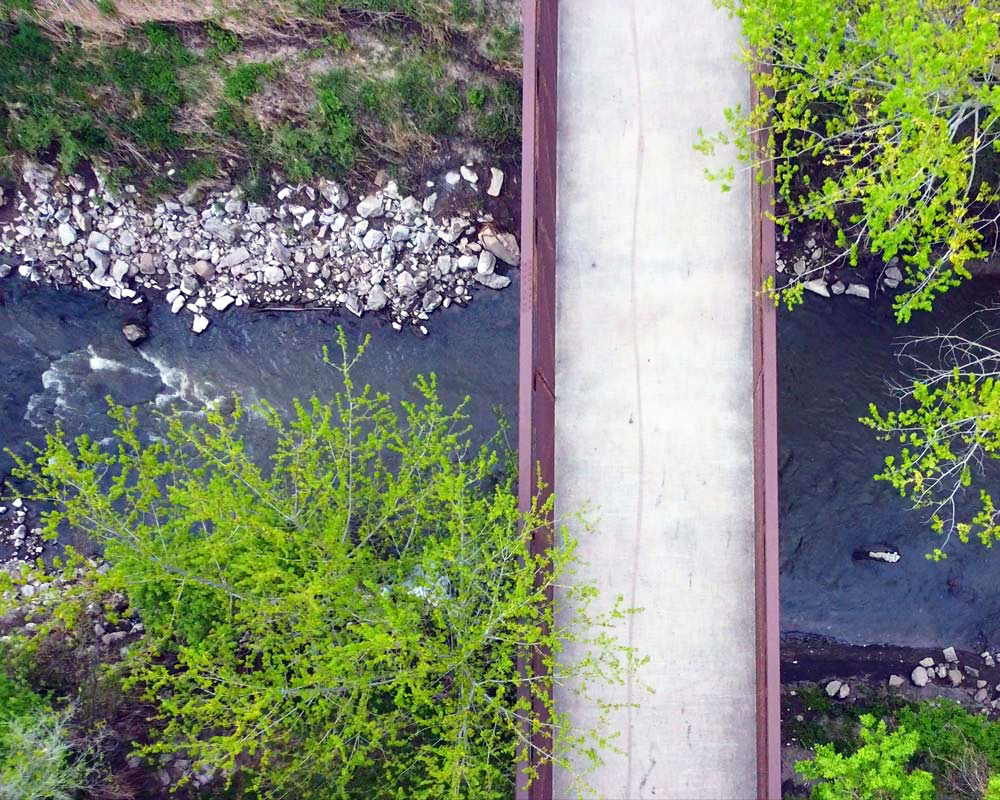

With the construction of the Great Plains Trails Network Connector Bridge in 2020, Wilderness Park has become even more popular and accessible for trail users. Hikers, cyclists, bird watchers, horseback riders and other park visitors find solace and peace among the big bluestem, Dutchman’s britches, trout lilies, and a wide variety of flora, fauna, insects, birds and critters.

Lincolnites are fortunate to have such a unique opportunity to enjoy and appreciate a natural area so close to home.

0

Acres

0

Miles long

0

Miles of trails

Drone Overview

Dense Forests

Salt Creek Beds

Meandering Trails

Bridge Crossings

Bird Viewing Areas

It’s your History

Wilderness Park has a very interesting history. Once home to the Otoe-Missouria and the Pawnee, some of the trails may even follow the same trails used by the Native Americans. Remnants of the past, all part of a lowland forest that has been intact and undisturbed for many years, still exist.

The Parks of Lincoln’s Early Days

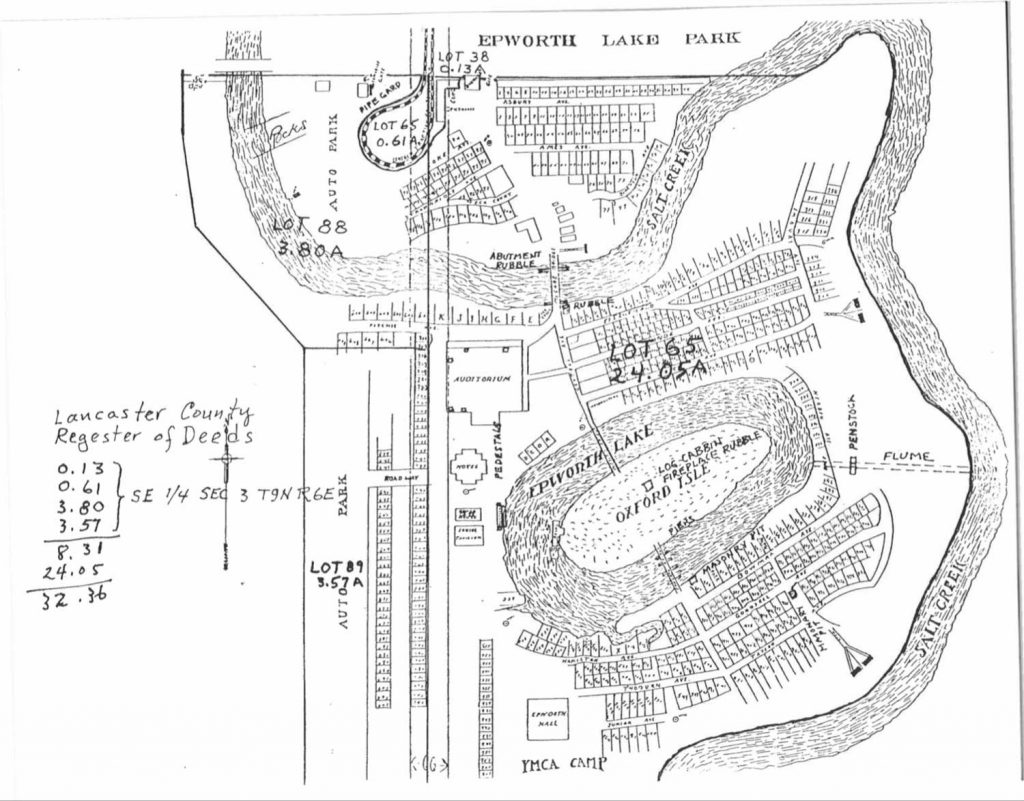

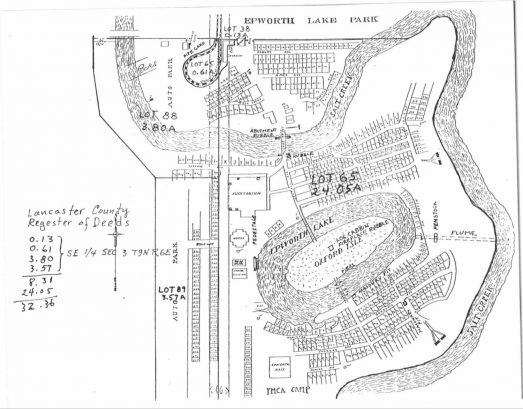

From the founding of Lincoln (1856) through the mid-20th century, the area of Wilderness Park was home to multiple attractions and parks. For many, memories of Epworth Lake Park, Lincoln Park and Electric Park are scrambled. But each location plays a part in the history of this area.

Lincoln Park was a private recreational enterprise established by local businessmen in 1894. Lincoln Park was bound by Van Dorn on the north, Calvert on the south, 1st Street on the east, and what would be SW 6th Street on the west. An article in the Nebraska State Journal on Nov. 22, 1895 states: “(Lincoln Park) is throughout a picturesque landscape of wooded hills, winding streams and grassy meadows that has from time to time been provided with magnificent drives, football and baseball fields, tennis courts, bathing and boating pavilions, swings, etc. Then there is the zoological department…and last, but not least, a race track.”

By 1915, Lincoln Park had a new owner and billed itself as Lincoln’s newest amusement resort, Electric Park. Attractions included operetta, acrobatics, live comedy, motion pictures, concerts, boating, vaudeville and cabarets. Admission was 10 cents per person. In 1916, 450 incandescent lights and 12 arc lights were added at the corner of 1st and Van Dorn Streets, making it truly an “Electric Park.” The attraction was closed by 1927.

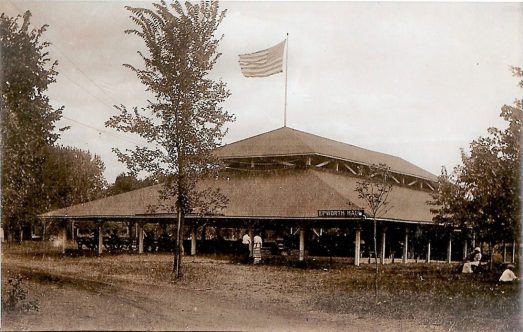

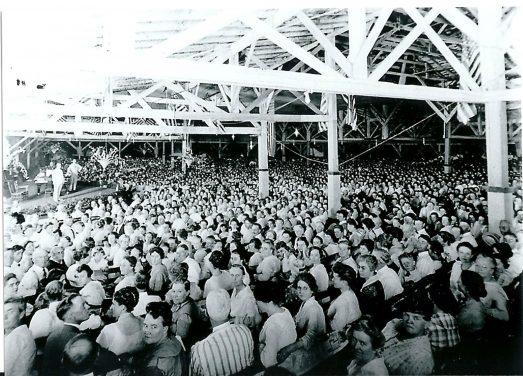

In the early 1900s, the portion of the park southeast of 1st and Calvert became known as Epworth Lake Park. This was a popular gathering spot and summer resort for the Methodist Church, featuring an open-air auditorium, campground, hotel, grocery store and Epworth Lake, the site of the park’s “Venetian Nights” in which families could rent ornately-decorated rafts and rowboats. Epworth Lake Park attracted thousands of visitors by train, street cars and trolley. The park also featured animal shows, musical acts, magicians and hosted popular speakers such as Theodore Roosevelt, William Jennings Bryan, Howard Taft, Booker T. Washington and Billy Sunday—reminiscent of those held in Chautauqua, New York.

In 1935, 14 inches of rain fell over the course of one week, causing flooding which destroyed most of the buildings in the park. Unsuccessful efforts were made to reopen the park, but American culture had changed with the advent of cars and mass communication. Families no longer needed to physically attend major speeches or concerts as they could now listen to them on the radio. Similarly, automobiles meant that families could quickly drive wherever they pleased for relatively low cost and no longer relied on the trains and streetcars which helped to make Epworth Lake Park thrive.

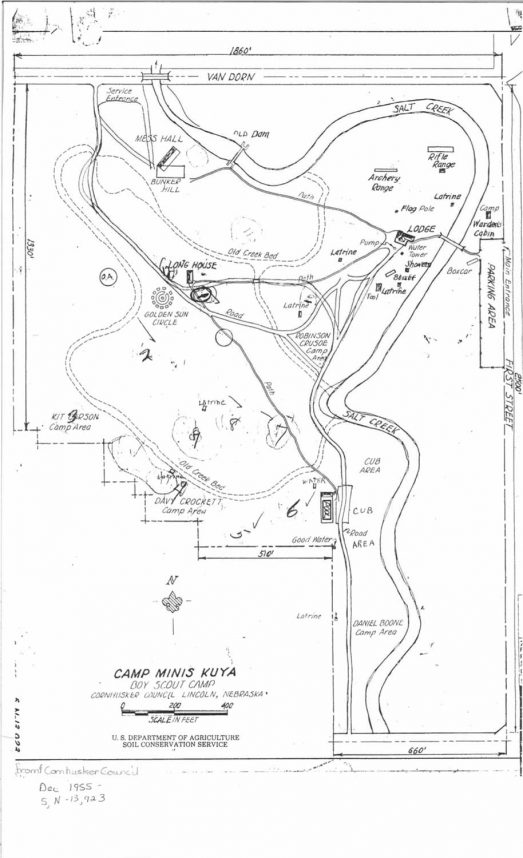

That same year, the Cornhusker Council of Boy Scouts began leasing the former Electric Park land and converted the park into its permanent camp. The council and volunteers built a swimming pool and longhouse while the Lion’s Club built a dining hall. The new facility was dubbed Camp Minis-Kuya, which some sources say can be translated from the Sioux as “salt water.” The camp closed in 1966.

In 1972, Camp Minis-Kuya, the former Epworth Lake Park, and other parcels were combined into what we know today as Wilderness Park.

We acknowledge that Wilderness Park rests on the traditional lands of the Otoe-Missouria and Pawnee Peoples, past and present, and we honor with gratitude the land itself and the people who have stewarded it throughout the generations. This calls us to commit to work in partnership with our Indigenous Peoples, continuing to learn how to be better stewards of the land we now inhabit as well.

How to use the park

As Lincoln’s largest park, Wilderness Park provides a unique opportunity for the public to enjoy, understand, and appreciate the value of a natural area within an urban setting. With its growing popularity and accessibility, the city of Lincoln recognizes the need to make it more user friendly, accessible, and educational to anyone seeking solace and recreation.

Few cities have an accessible, primitive park area that provides an opportunity for recreation and reflection, as well as an economic attraction to families seeking to live and work in Lincoln.

When entering the park via the various trailheads, park users can use the kiosk and trail signage to navigate to their desired destinations.

Wilderness Park has provided a timeless retreat over five decades for my family. From the meandering stream corridor to the woodsy canopy, it is a place of discovery and sharing that we’ve always loved.

Explore the Park

Wilderness Park trailheads are a gateway to the unique promise of the Wilderness Park experience. Each trailhead offers a new experience every season of the year and for each type of adventurer.